Example – Top Artists¶

This is a very simplified case of something we do at Spotify a lot. All user actions are logged to Google Cloud Storage (previously HDFS) where we run a bunch of processing jobs to transform the data. The processing code itself is implemented in a scalable data processing framework, such as Scio, Scalding, or Spark, but the jobs are orchestrated with Luigi. At some point we might end up with a smaller data set that we can bulk ingest into Cassandra, Postgres, or other storage suitable for serving or exploration.

For the purpose of this exercise, we want to aggregate all streams, find the top 10 artists and then put the results into Postgres.

This example is also available in examples/top_artists.py.

Step 1 - Aggregate Artist Streams¶

class AggregateArtists(luigi.Task):

date_interval = luigi.DateIntervalParameter()

def output(self):

return luigi.LocalTarget("data/artist_streams_%s.tsv" % self.date_interval)

def requires(self):

return [Streams(date) for date in self.date_interval]

def run(self):

artist_count = defaultdict(int)

for input in self.input():

with input.open('r') as in_file:

for line in in_file:

timestamp, artist, track = line.strip().split()

artist_count[artist] += 1

with self.output().open('w') as out_file:

for artist, count in artist_count.iteritems():

print(artist, count, file=out_file)

Note that this is just a portion of the file examples/top_artists.py.

In particular, Streams is defined as a Task,

acting as a dependency for AggregateArtists.

In addition, luigi.run() is called if the script is executed directly,

allowing it to be run from the command line.

There are several pieces of this snippet that deserve more explanation.

Any

Taskmay be customized by instantiating one or moreParameterobjects on the class level.The

output()method tells Luigi where the result of running the task will end up. The path can be some function of the parameters.The

requires()tasks specifies other tasks that we need to perform this task. In this case it’s an external dump named Streams which takes the date as the argument.For plain Tasks, the

run()method implements the task. This could be anything, including calling subprocesses, performing long running number crunching, etc. For some subclasses ofTaskyou don’t have to implement therunmethod. For instance, for theJobTasksubclass you implement a mapper and reducer instead.LocalTargetis a built in class that makes it easy to read/write from/to the local filesystem. It also makes all file operations atomic, which is nice in case your script crashes for any reason.

Running this Locally¶

Try running this using eg.

$ cd examples

$ luigi --module top_artists AggregateArtists --local-scheduler --date-interval 2012-06

Note that top_artists needs to be in your PYTHONPATH, or else this can produce an error (ImportError: No module named top_artists). Add the current working directory to the command PYTHONPATH with:

$ PYTHONPATH='.' luigi --module top_artists AggregateArtists --local-scheduler --date-interval 2012-06

You can also try to view the manual using --help which will give you an

overview of the options.

Running the command again will do nothing because the output file is already created. In that sense, any task in Luigi is idempotent because running it many times gives the same outcome as running it once. Note that unlike Makefile, the output will not be recreated when any of the input files is modified. You need to delete the output file manually.

The --local-scheduler flag tells Luigi not to connect to a scheduler

server. This is not recommended for other purpose than just testing

things.

Step 1b - Aggregate artists with Spark¶

While Luigi can process data inline, it is normally used to orchestrate external programs that perform the actual processing. In this example, we will demonstrate how top artists instead can be read from HDFS and calculated with Spark, orchestrated by Luigi.

class AggregateArtistsSpark(luigi.contrib.spark.SparkSubmitTask):

date_interval = luigi.DateIntervalParameter()

app = 'top_artists_spark.py'

master = 'local[*]'

def output(self):

return luigi.contrib.hdfs.HdfsTarget("data/artist_streams_%s.tsv" % self.date_interval)

def requires(self):

return [StreamsHdfs(date) for date in self.date_interval]

def app_options(self):

# :func:`~luigi.task.Task.input` returns the targets produced by the tasks in

# `~luigi.task.Task.requires`.

return [','.join([p.path for p in self.input()]),

self.output().path]

luigi.contrib.hadoop.SparkSubmitTask doesn’t require you to implement a

run() method. Instead, you specify the command line parameters to send

to spark-submit, as well as any other configuration specific to Spark.

Python code for the Spark job is found below.

import operator

import sys

from pyspark.sql import SparkSession

def main(argv):

input_paths = argv[1].split(',')

output_path = argv[2]

spark = SparkSession.builder.getOrCreate()

streams = spark.read.option('sep', '\t').csv(input_paths[0])

for stream_path in input_paths[1:]:

streams.union(spark.read.option('sep', '\t').csv(stream_path))

# The second field is the artist

counts = streams \

.map(lambda row: (row[1], 1)) \

.reduceByKey(operator.add)

counts.write.option('sep', '\t').csv(output_path)

if __name__ == '__main__':

sys.exit(main(sys.argv))

In a typical deployment scenario, the Luigi orchestration definition above as well as the Pyspark processing code would be packaged into a deployment package, such as a container image. The processing code does not have to be implemented in Python, any program can be packaged in the image and run from Luigi.

Step 2 – Find the Top Artists¶

At this point, we’ve counted the number of streams for each artists, for the full time period. We are left with a large file that contains mappings of artist -> count data, and we want to find the top 10 artists. Since we only have a few hundred thousand artists, and calculating artists is nontrivial to parallelize, we choose to do this not as a Hadoop job, but just as a plain old for-loop in Python.

class Top10Artists(luigi.Task):

date_interval = luigi.DateIntervalParameter()

use_hadoop = luigi.BoolParameter()

def requires(self):

if self.use_hadoop:

return AggregateArtistsSpark(self.date_interval)

else:

return AggregateArtists(self.date_interval)

def output(self):

return luigi.LocalTarget("data/top_artists_%s.tsv" % self.date_interval)

def run(self):

top_10 = nlargest(10, self._input_iterator())

with self.output().open('w') as out_file:

for streams, artist in top_10:

print(self.date_interval.date_a, self.date_interval.date_b, artist, streams, file=out_file)

def _input_iterator(self):

with self.input().open('r') as in_file:

for line in in_file:

artist, streams = line.strip().split()

yield int(streams), int(artist)

The most interesting thing here is that this task (Top10Artists) defines a dependency on the previous task (AggregateArtists). This means that if the output of AggregateArtists does not exist, the task will run before Top10Artists.

$ luigi --module examples.top_artists Top10Artists --local-scheduler --date-interval 2012-07

This will run both tasks.

Step 3 - Insert into Postgres¶

This mainly serves as an example of a specific subclass Task that doesn’t require any code to be written. It’s also an example of how you can define task templates that you can reuse for a lot of different tasks.

class ArtistToplistToDatabase(luigi.contrib.postgres.CopyToTable):

date_interval = luigi.DateIntervalParameter()

use_hadoop = luigi.BoolParameter()

host = "localhost"

database = "toplists"

user = "luigi"

password = "abc123" # ;)

table = "top10"

columns = [("date_from", "DATE"),

("date_to", "DATE"),

("artist", "TEXT"),

("streams", "INT")]

def requires(self):

return Top10Artists(self.date_interval, self.use_hadoop)

Just like previously, this defines a recursive dependency on the previous task. If you try to build the task, that will also trigger building all its upstream dependencies.

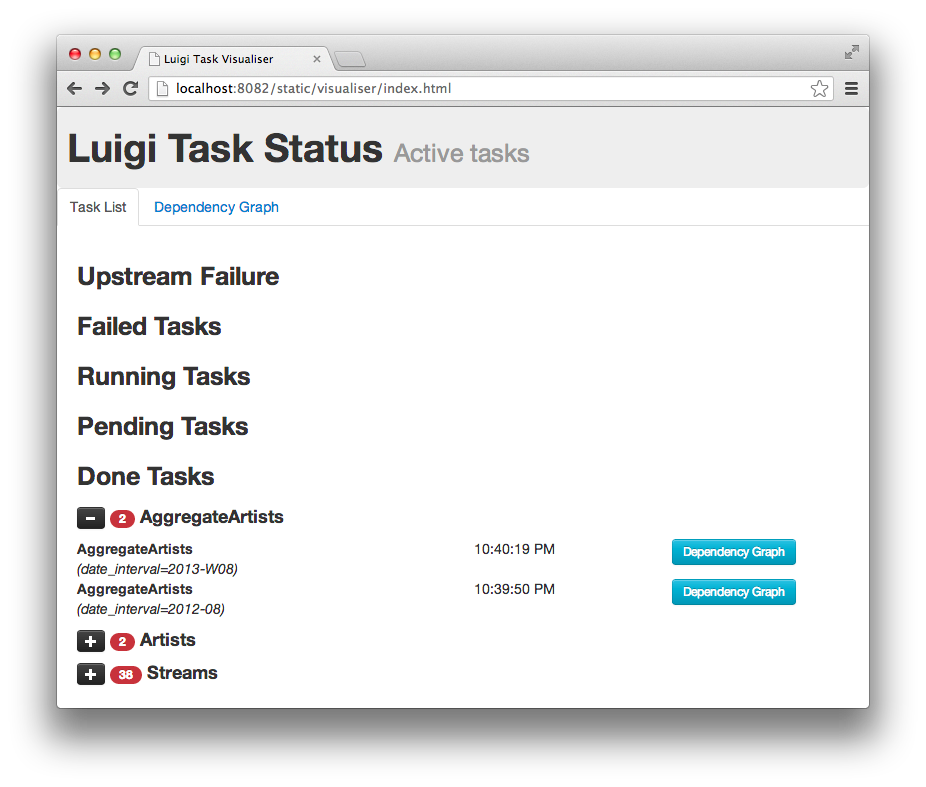

Using the Central Planner¶

The --local-scheduler flag tells Luigi not to connect to a central scheduler.

This is recommended in order to get started and or for development purposes.

At the point where you start putting things in production

we strongly recommend running the central scheduler server.

In addition to providing locking

so that the same task is not run by multiple processes at the same time,

this server also provides a pretty nice visualization of your current work flow.

If you drop the --local-scheduler flag,

your script will try to connect to the central planner,

by default at localhost port 8082.

If you run

$ luigid

in the background and then run your task without the --local-scheduler flag,

then your script will now schedule through a centralized server.

You need Tornado for this to work.

Launching http://localhost:8082 should show something like this:

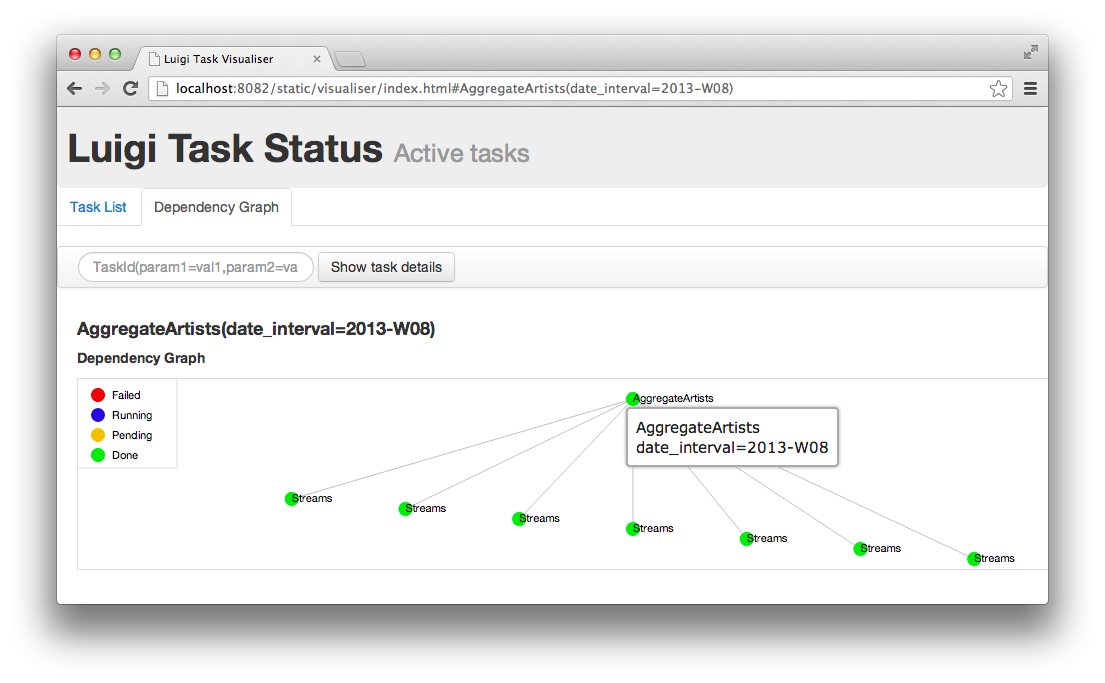

Web server screenshot Looking at the dependency graph for any of the tasks yields something like this:

Aggregate artists screenshot

In production, you’ll want to run the centralized scheduler. See: Using the Central Scheduler for more information.